Eureka Company

During all of this activity, Armes notes that the ownership of the Oxmoor furnaces had reverted to Henry DeBardeleben, who had left in disgrace and returned of his own volition to Prattville, home of his father-in-law's cotton gin factory. After the successful experiment of February 28, 1876, Sloss and Thomas moved quickly to reorganize the Eureka enterprise with new leadership and to purchase all rights and interests of the company -- negotiating with DeBardeleben. It should be recalled that as Pratt's son-in-law, and now heir, since Pratt had died in 1873, DeBardeleben owned not only the furnaces but most of the iron property of Red Mountain "from Grace's Gap to Bessemer" [Armes, p. 261]

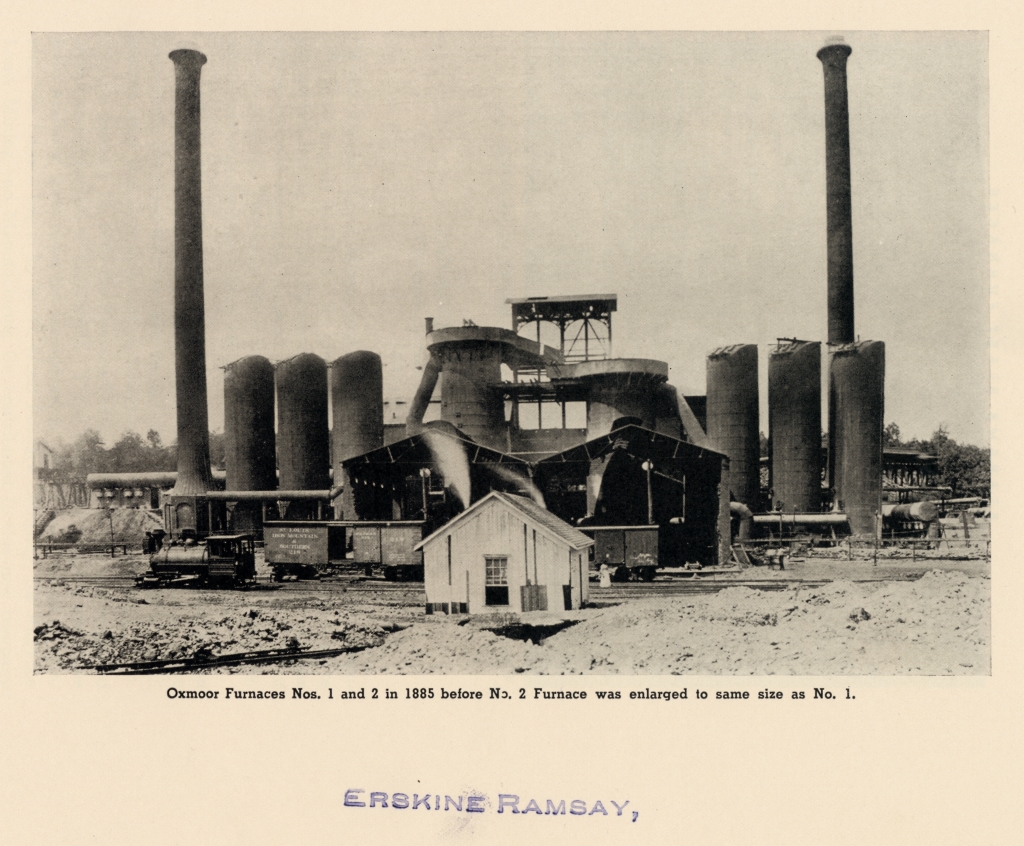

Sloss and Thomas obtained options, and organized a new company including interests from Louisville (Sloss) and from Cincinnati (Thomas). Armes tells us that the charter of the Eureka company was changed before the new owners took over. Thomas began to make changes to the plant. He built "two new stacks, the construction at Helena of one hundred coke ovens, and the building at the Oxmoor plant of an expensive battery of patent ovens operated by machinery. The capacity of the new furnaces was about four times as great as that of the old ones, and a better quality of metal was the result. Furnace No. 2 was blown in March, 1876, while No. 1 was not completed until July of 1877."

Woodward's account states that "[the] experiment was a

success and the No. 1 furnace was rebuilt to use coke and completed in July

1877. Both the furnaces were now iron shell stacks (No. 1 - 60 x 16 feet,

No. 2 - 60 x 14 feet) but still had sandstone hearths. With rebuilding of

the furnaces, the mines at Helena were increased in capacity and 100 beehive

ovens were constructed there. A small battery of Belgian coke ovens was

also erected at the furnace to coke Cahaba coal." [Are these upper

left of loco at right?]

Woodward's account states that "[the] experiment was a

success and the No. 1 furnace was rebuilt to use coke and completed in July

1877. Both the furnaces were now iron shell stacks (No. 1 - 60 x 16 feet,

No. 2 - 60 x 14 feet) but still had sandstone hearths. With rebuilding of

the furnaces, the mines at Helena were increased in capacity and 100 beehive

ovens were constructed there. A small battery of Belgian coke ovens was

also erected at the furnace to coke Cahaba coal." [Are these upper

left of loco at right?]

Armes discusses an interesting bit of operational history that also reflects an interesting characteristic of the Red Mountain ores. After the improvements to the furnaces, production continued, but there were problems with the pig iron. The previously mentioned John Veitch was head furnace man under Sloss and Thomas; Levin Goodrich had left the area and returned to Tennessee's iron industry near Nashville.

The problem according to Armes account had to do with the quality of iron and the amount of lime. Veitch's work caused either a "silver gray" or "rotten iron" which was too soft for the market. An iron making expert from St. Louis, named Ferry, was brought in, and he made changes resulting in a hard and brittle iron which was as unsatisfactory as the soft iron had been. Ferry returned to St. Louis and Veitch resigned.

A man named John Shannon had come to Oxmoor, with experience in other iron markets, including Georgia. He became head furnace man when Veitch refused overtures that he return. Shannon was able to discern that the ore itself had changed, with the continued mining at greater depth into Red Mountain, resulting in an inferior pig iron. Years later, this is noted in "Tennessee Coal Iron and Railroad Company, 1900", available at the Birmingham Public Library, rare book collection, p. 114:

"...the [iron] ore is found outcropping at the summit of the [Red] mountain, and pitches to the southeast very uniformly on a slope of from twenty to thirty degrees. The vein runs up to 22 feet in thickness, but for economic reasons the workings are usually confined to the upper 10 feet of the vein. The ore near the outcrop, and extending down sometimes several hundred feet on the slope, carries but a small percentage of lime, and is known as "soft" ore; below this line, the "hard" ore sets in, carrying lime, often sufficient in quantity to make the ore self-fluxing, and running quite uniformly in quality and thickness."

John Shannon figured this out on his own by observation, and he improved the pig iron by reducing the quantity of lime added to the furnace, and thereby met the market demand with the pig iron made at Oxmoor. [Armes, p. 263] Shannon's reputation rightly improved from this experience, and he continued successfully in a series of positions, until his death in 1897 working at the "Big Four" furnaces of TCI at Ensley.

Woodward's account of this period is similar, but not quite so positive. He states,

"Shortly after the coke iron was made [1876], two groups - one from Louisville and the other one from Cincinnati - sought control of the operation. Neither party was successful and for the next few years the plant was operated to the dissatisfaction of everyone. David Sinton of Cincinnati finally gained control in 1886 and operated the property until it was sold on October 18, 1890 to the DeBardeleben Coal and Iron Co. Oxmoor No. 1 had been rebuilt in 1885 and in 1886 the No. 2 furnace was enlarged to the same size as No. 1, 75 x 17 feet. The combined output of the furnaces was thus increased to about 250 tons per day."

The following image is from Woodward, "Alabama Blast Furnaces", p.109, from the author's collection. As noted in the caption, the furnace on the right, No. 2, is under renovation, as indicated by the work being done on the top of the stoves on the right of the picture.